In a full-page opinion piece in today’s Sunday New York Times, Bret Stephens calls the year since October 7, 2023, “The Year American Jews Woke Up” to the inevitability of antisemitism. Antisemitism, along with, (though Stephens does not mention them) anti-Muslim, anti-Palestinian, and anti-Arab bigotries, have all surged in this country and around the world in response to a year of atrocities and atrocious responses to atrocities in — and around — the territory between the (Jordan) river and the (Mediterranean) sea, which is ruled by the State of Israel and claimed by the Palestinian people.

For Stephens, only antisemitism has surged. He claims it has reinforced his pride in being Jewish, one thing that he and I share, though apparently for different reasons. I too feel that “to have been born a Jew is the single most fortunate thing that has ever happened to me,” and that “It is a priceless, moral, spiritual, intellectual inheritance from my ancestors, some of whom were slaughtered for it.”

But what is that inheritance? According to Stephens:

To be a Jew obliges us to many things, particularly our duty to be our brother’s and sister’s keeper. That means never to forsake one another, much less to join in the vilification of our own people.

To be a Jew is to show solidarity with other Jews, which means, he says, “to embrace — often as a thoughtful critic, but never as a hateful scold — the great, complicated, essential project of a Jewish state.”

The current state of Israel, however, is not the first Jewish state. Here is what one critic said about the Kingdom of Judah around 609-605 B.C.E:

Why is this people — Jerusalem— rebellious

With a persistent rebellion?

They cling to deceit.

They refuse to return.

They do not speak honestly.

No one regrets his wickedness

And says, “What have I done?”

Saying, “All is well, all is well,”

When nothing is well.

They have acted shamefully;

They have done abhorrent things —

Yet they do not feel shame,

They cannot be made to blush.

Assuredly, they shall fall among the falling,

They shall stumble at the time of their doom.

Are these the words of a “thoughtful critic?” A “hateful scold?” In any case, they are the words of the prophet Jeremiah (8:5-6, 11-12).

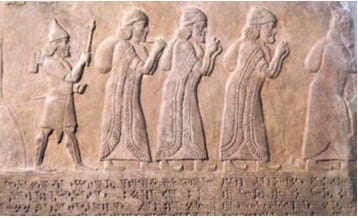

Jeremiah’s prophecy came to pass. In 586 B.C.E. Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon, conquered and laid waste to Jerusalem and the holy sanctuary. His armies forced the people into exile across the River Euphrates. Jeremiah was there to mourn and interpret it (Lamentations 1: 3-5):

Judah has gone into exile

Because of misery and harsh oppression;

When she settled among the nations,

She found no rest;

Her enemies are now the masters,

Her foes are at ease,

Because the Lord has afflicted her

For her many transgressions.

This passage expressed a consensus of the prophets about the fall of the first temple and the Kingdom of Judah. I am no Biblical scholar, but I have listened to many readings from the Prophets as haftarah portions after the reading from the Torah, and I cannot recall any prophets who remonstrate with the People of Israel for insufficient loyalty to the state.

Less than a century later, Cyrus, the Zoroastrian Shah of Persia, conquered Babylon. He authorized the exiles to return to their land — not to build a state, but to rebuild the Temple and the community of Israel, while living in peace with the other peoples of the land. The Temple and the sacrifices endured for centuries, while scholars began to develop the teachings of law and lore that are still the foundation of Judaism.

The Persian empire fell to Alexander of Macedon, whose successors divided his Hellenistic empire. In 141 B.C.E. the revolt of the Macabees against the Hellenistic rulers of Syria established a new Jewish dynasty, the Hasmoneans. That state’s autonomy expanded for a few decades (this was before the world of sovereign nation-states), but it ultimately had to come to terms with the rising power of Rome. In 37 B.C.E. Judea became a Roman client state under King Herod the Great and a province of Rome in 6 C.E.

Misrule under the emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 68 C.E., provoked the Great Revolt of the Jews that began in 66. Nero sent his top general, Vespasian, to subdue the country. After conquering Galilee, Vespasian laid siege to Jerusalem. While still engaged in the siege, he succeeded Nero after the latter’s death in 68 C.E., leaving the military command to his son, Titus. Two years later, in 70 C.E., Titus laid waste to the city and destroyed the Second Temple

.Today the State of Israel commemorates the resistance to Rome at Masada, where, according to the historian Flavius Josephus, a commander of the Great Revolt who surrendered to the Romans, 967 Jews held out for three years after the fall of Jerusalem. When they saw they could not avoid defeat, they chose collective suicide rather than submit to their Roman besiegers.

According to the website of the Masada National Park:

Masada, a name synonymous with bravery and freedom, stands tall amidst the Judean Desert’s rugged landscape. The fortress, built by King Herod and later the site of the Jewish rebels’ final stand against Rome, tells a tale of resilience that resonates through time.

At their induction into the Israel Defense Forces, soldiers end their oath with a phrase from Yitzhak Lamdan’s poem, “Masada”: “Masada shall not fall again.” (“Masada lo tipol shenit.”)1

The reverence for Masada’s defenders dates only to the 1930s. Throughout Jewish history, tradition did not blame Roman power (let alone “antisemitism”) for the fall of the Second Temple. Tractate Yoma of the Babylonian Talmud explains (p. 9b):

Why was the first Sanctuary destroyed? because of three [evil] things which prevailed there: idolatry, immorality, and bloodshed….But why was the second Sanctuary destroyed. . .? Because therein prevailed hatred without cause. That teaches that groundless hatred is considered as of even gravity with the three sins of idolatry, immorality, and bloodshed together.”

What was this “hatred without cause?” Practically the only source on these events is Josephus’s Wars of the Jews. Yigael Yadin, the former IDF chief of staff who headed the excavations at Masada in the 1960s, wrote that the excavations confirmed that Josephus’ account is “very faithful.”2

Josephus states that the holdouts in Masada were members of the Sicarii, an extremist faction named after the sicae (small daggers) that they carried under their cloaks to assassinate their (usually Jewish) enemies. Visitors to Masada coming from the north down the Jordan Valley pass through the oasis town of Ein Gedi. Here is Josephus’s account of what the defenders of Masada did there:

There was a fortress of very great strength not far from Jerusalem, which had been built by our ancient kings, . . . It is called Masada. Those who were called Sicarii had taken possession of it formerly; but at this time they overran the neighboring countries, aiming only to procure to themselves necessities; . . .and at the feast of unleavened bread, which the Jews celebrate in memory of their deliverance from Egyptian bondage, . . . they came down by night … and overran a certain small city called Engaddi; —They … cast [those who could fight them] out of the city. As for such as could not run away, being women and children, they slew of them above seven hundred. . . . And indeed these men laid all the villages that were about the fortress waste, and made the whole country desolate; while there came to them every day from all parts not a few men who were as corrupt as themselves.3

In a single incident, the Sicarii of Masada, without benefit of the firepower of modern weaponry, killed more than half the number of Jewish civilians that Hamas and its allies did on October 7, 2023.

For nearly two thousand years, Jews did not consider the Sicarii of Masada as models for future generations. They recognized that the man who did the most to save Jewish religion, culture, and identity through the fall of the Second Temple was Rabban Yochanan Ben Zakkai, the greatest scholar of the age. The story of Ben Zakkai has come down to us in The Fathers of Rabbi Natan (Avot de-Rabbi Natan), a commentary on Pirkei Avot, The Chapters of the Fathers, which was probably compiled in the Babylonian academies during 700-900 C.E.

The account of the destruction of the Second Temple given in Avot de-Rabbi Natan supports the judgment of the redactors of Tractate Yoma. Neither mentions hatred of the Jews, let alone antisemitism, as the reason for the destruction of Jerusalem. It is instead ascribed to the factional militancy and unwillingness to compromise of the Zealots in Jerusalem:

When Vespasian came to destroy Jerusalem, he said to the inhabitants, “Fools, why are you asking me to destroy this city? And why do you seek to destroy this city and why do you seek to burn the Temple? For what do I ask of you but that you send me one bow or one arrow [tokens of submission], and I shall go off from you.”

They said to him: “Just as we went forth against the first two who were before you [Cestius Gallus and Gessius Florus] and slew them, so shall we go forth against you and slay you.”

When Rabban Yohanan Ben Zakkai heard this, he sent for the men of Jerusalem, and said to them, “My children, why do you want to destroy this city and why do you seek to burn the Temple? For what is it that he asks of you? Verily he asks naught of you save one bow or one arrow, and he will go off from you.”

They said to him, “Even as we went forth against the two before him and slew them, so shall we go forth against him and slay him.”

When Ben Zakkai repeated this advice for three days, and the fighters did not listen, he instructed his students to carry him out of the city hidden in a coffin. On his instructions, they took him to Vespasian. When Vespasian asked what he wanted, He said “Yavne [a town on the coast about 30 miles west of Jerusalem], where I might go and teach my disciples.” Vespasian answered, “Go; and whatever you wish to do, do.”

In Yavne Ben Zakkai laid the basis for Judaism without a temple, a religion based on study, law, and prayer, without animal sacrifice. The Avot de-Rabbi Natan recounts that when his student, Rabbi Joshua, was mourning over the destruction of the temple, asking what would now atone for the sins of Israel, Ben Zakkai said, “We have another atonement, effective as this, And what is it? It is deeds of lovingkindness (gemilut hasadim), as it is said (Hosea 6:6), ‘I desire mercy and not sacrifice.’”4

Throughout Jewish history, the Sicarii, if they were remembered at all, were remembered for their “baseless hatred,” while Rabban Yohanan Ben Zakkai was venerated for enabling the Jewish people to transform their religion and identity for a new age.

The Bible tells of many enemies of the Children of Israel and the Jewish people, from Amalek to Haman, and history offers many more examples. But the prophets and rabbis did not consider Nebuchadnezzar and Vespasian as antisemites. They taught that sometimes the Jewish people, like others, can create a state and society capable of such evil, that God himself sends an army to destroy it.

And what is that evil?

The Torah teaches, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” In August 1963, my mother took me to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom with the Philadelphia delegation of the American Jewish Congress. The last speaker before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was Rabbi Joachim Prinz, President of the American Jewish Congress. He said:

Our fathers taught us thousands of years ago that when God created man, he created him as everybody's neighbor. Neighbor is not a geographic term. It is a moral concept. It means our collective responsibility for the preservation of man's dignity and integrity.

Bret Stephens attributes the hostility toward Jews that he has observed over the last year to the fact “That there will always be those who hate us.” For him, Israel deserves impunity, and Jews are always innocent victims. Nowhere in his shameful article does Stephens breathe a word about the State of Israel’s assaults on the dignity and integrity — not to mention lives— of our neighbors, the Palestinians.

Masada may fall again, even if today’s Sicarii do not realize that they are committing suicide. If it does, a modern Ben Zakkai will have to teach us to live without a super-militarized, supremacist state.

Leon I. Yudkin, Isaac Lamdan: A Study in Twentieth Century Hebrew Poetry (London: Horovitz Publishing, Studies in Modern Hebrew Literature, 1971), pp. 199-207.

Yigael Yadin, Masada: Herod’s Fortress and the Zealots Last Stand (New York: Random House, 1966, p. 42.

Flavius Josephus, Wars of the Jews, Book IV, Chapter VII, paragraph 2, in Josephus: Complete Works, translated by William Whiston (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications 1970 [first edition 1960], p. 537.

The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan, translated by Judah Goldin, Yale Judaica Series Vol. X (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,1967 [first edition 1955], pp. 34-36. Judah Goldin taught my mother’s confirmation class at the Germantown Jewish Center in Philadelphia in 1938, and I attended a course he taught on Mishna as a freshman at Yale in the fall of 1967.

Wonderful! Thank you for this.

Excellent piece Barney, learnt a lot from this.